We often take roads for granted, and we seldom think about them unless we're stuck in traffic because of an accident or road work. They're just there for our convenience. But roads have stories and backstories that are interesting. For example, learning how a road is built and who built it is often surprising. Knowing how much it costs is often shocking.

In this blog, we will explore the primary road in Blawenburg, County Route 518 (aka Georgetown-Franklin Turnpike), its connection with State Road 206, and its other access roads.

Georgetown-Franklin Turnpike circa 1900

The Earliest Road

The earliest road through Blawenburg was just a path used by the Lenni Lenape Native Americans. They lived in New Jersey for many centuries before the European settlers arrived, and they created paths to travel from village to village in the easiest way possible. Their pathway from the Delaware River near what is now Trenton was called the Wissamonson Path. A portion of this path traveled along Blawenburg Ridge, where Route 518 is today. It was a well-worn path that interconnected with other paths that led to the shore areas where the Lenape spent their summers.

Undoubtedly, this path was narrow, since the Lenape only had walking and canoes as their means of transportation. They had no horses, so the pathway would not be wide. (Learn more about why they had no horses in Fact 1 below.)

Arrival of the Dutch

The old Lenape path must have been rough traveling for the Dutch settlers—narrow, abundant potholes, and many obstacles, such as fallen trees and limbs. In the early 1700s, tracts of land known patents were sold and resold by land speculators. John Van Horne from New York purchased all the land along the Lenape path from the Province Line Road in Stoutsburg at the Hopewell Township border to Rocky Hill. He then sold off smaller plots of land to Dutch farmers with names like Covenhoven, Blaw, and Nevius in the first half of the 1700s.

It is unclear whether Van Horne or other speculators made any attempt to improve the pathway so prospective buyers could get to the area more easily. At best, it must have been a rough ride.

Access Roads

Michael Blaw, the son of homesteader John Blaw, built his mill along Bedens Brook around 1742, providing a service needed by the Dutch farmers. There was only a rough pathway to get from the main road on Blawenburg Ridge south to the mill. The Blaws, who all lived close to Bedens Brook, took it upon themselves to improve the pathway to the mill. Their pathway, which is still in use today, is known as Great Road.

Residents of Princeton noted that this road could be helpful in traveling to and from town, so they extended it south through Cedar Grove, an extinct community south of Cherry Valley Road. This community was located where the Tenacre Foundation is today. For a time, this part of the extended Great Road was known as Blawenburg-Cedar Grove Road. This land was once owned by Benjamin Franklin. The Princeton Road Department connected the Great Road extension to Elm Road in Princeton.

Route 601, also known as Belle Mead-Blawenburg Road,

looking south toward Blawenburg

Belle Mead-Blawenburg Road is a similar example of an extension road. With Great Road complete to Princeton, adding a road that would go north to Belle Mead made sense. It is a Somerset County road and has also been called County Route 13. Today, this road serves as a bypass around Princeton and Montgomery for the more crowded Route 206.

A Turnpike through Blawenburg

By 1816, people complained about the condition of the road that led from Lambertville along the Delaware River to New Brunswick. While it may seem hard to believe today, it was a major stagecoach route from Philadelphia to New York. The road was showing wear from heavy travel and bad weather that left many ditches from the water run-off. Since this was the turnpike era in the nation, the communities along its route agreed to improve the road and make it a turnpike. (Learn more about turnpikes in Fact 2 below.)

The road from Georgetown (Lambertville) to Franklin (Kendall Park/Route 27) was started in 1816 before a single house was built in the Village of Blawenburg. It was up to Montgomery Township to maintain the road, but by 1840, the concept of the multi-community turnpike was abandoned. The turnpike is still here and its name is the same; however, the authority for its maintenance abides with Somerset and Hunterdon counties. It is known as County Route 518, as well as Georgetown-Franklin Turnpike today.

Construction of Routes 206 and 518 near Bolmer's Corner in 1913

A New Way to Build Roads

At the turn of the last century, the automobile was all the rage. They couldn't sell cars fast enough. The dirt roads that had worked well for horses and carriages didn't work so well for cars. The new horseless carriages needed a smooth surface to perform well.

In New Jersey, both the county and state administrations were eagerly trying to find sufficient funds to create and adapt roads to meet the need for safe car travel. One idea emerged that would soften the impact on taxpayers, and the legislature loved it — convict labor camps. Using this idea, the state would set up camps and bring in convicted prisoners to work on the roads. They tried this with success at Andover in Sussex County, and then established a road camp south of Rocky Hill to join other existing roads together, making a continuous road from the trolley tracks on Bayard Lane in Princeton to Somerville.

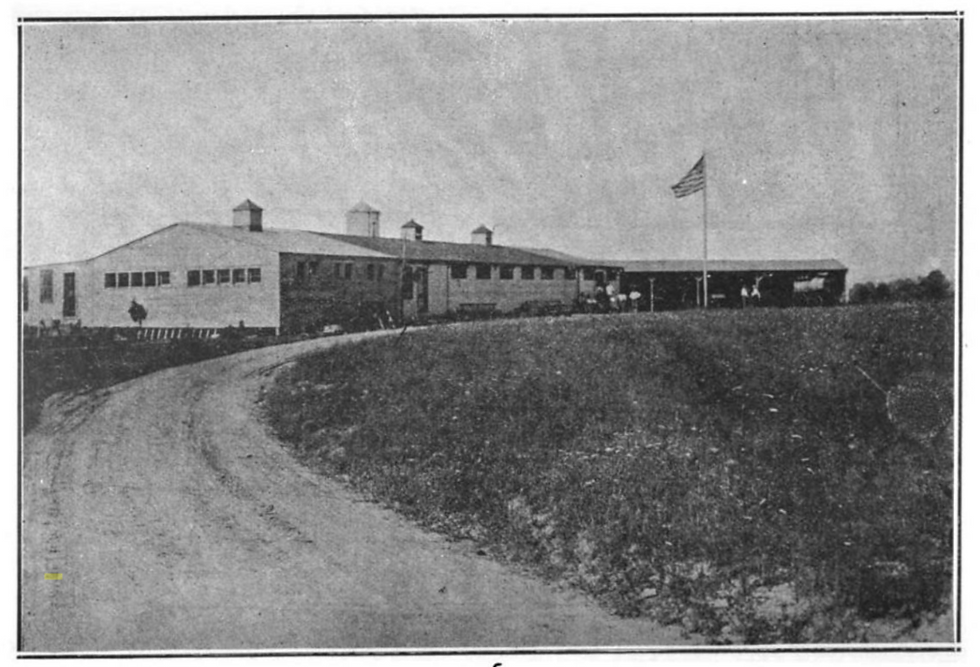

Road Camp No. 2 at the Douglass Farm, Rocky Hill

In June, 1913, the camp was begun on a farm south of Rocky Hill near the Princeton border. The Douglass Farm was off Princeton Avenue near the intersection with Mount Lucas Road. Until the camp buildings were completed, men were brought by "motor truck" from the New Jersey State Prison in Trenton to work on the road. When the housing was completed in November, 1913, the men were moved to what was called State Road Camp No. 2, also known as Rocky Hill Convict Camp No. 2 or Road Camp 2 at Rocky Hill.

As you might expect, the prisoners' arrival was controversial. Area residents feared the worst—robberies, muggings, and breakouts. The prison administration assured the residents that all would be calm because these prisoners were within a few months of their release, so it would be foolish for them to jeopardize their freedom with bad behavior.

All Was Not Well at the Road Camp

The road camp prisoners did not interact with the local communities as feared; however, they exacted poor behavior on each other. Multiple newspaper articles from that period show many disagreements and fights that kept the camp in turmoil.

One major incident filled the newspapers for almost a year. In October 1915, two convicts, Alonso Williams, 24, and Benjamin Wooley, 36, quarreled after a baseball game on a Sunday afternoon. Williams threatened to "get" Wooley, and he followed through on his threat. He went to the bunkhouse and struck Wooley over the head with a baseball bat. Wooley was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Williams was tried in Somerville and eight prisoners said they witnessed Williams strike Wooley. Williams was convicted of first degree murder and was sentenced to up to 30 years in prison.

Completing the Road

The road they were refurbishing was from Bayard Lane in Princeton to Bolmer's Corner (Route 206 and 518). Mercer County donated the land on the portion of the road in Princeton, while Montgomery farmers donated strips of land for their section.

Stone for this road, a diabase (trap rock), was likely acquired from a local quarry between Rocky Hill and Kingston owned by Trap Rock Industries that is still operational today. This quarry has existed since the middle of the 19th century. The state borrowed a stone crusher from Princeton to make the quarry stone more suitable for paving.

The legislature provided much of the money for the road projects; however, they balked at the rising costs and refused to appropriate more funds. They said it was up to the township to pay for surveying the land, an essential part of the project. Local farmers decided they wanted this project done, so they each pitched in $25 to cover the $300 surveying cost!

Part of the deal was to pave the Blawenburg Road from Bolmer's Corner to Blawenburg, a 2.7-mile project. Grading began, but was stopped for lack of funds. This greatly concerned the township committee, so three men, T. A. Bolmer, Edgar Van Zandt, and Henry Duryea, petitioned Governor Fiedler on behalf of the township to acquire the funds to pave the road to Blawenburg.

They reminded the governor that they had already given the land for the project and paid for the surveying. They had haggled over the project's completion for a long time and insisted that the state or county needed to "macadamize" Blawenburg Road. The Governor agreed with them. Finally, in 1922, perhaps with a nudge from the governor, the Somerset Freeholders awarded a $17,990.00 contract to Richards and Gaston of Somerville to pave the road.

Moving the Camp

Road camps were to be set up for temporary use and dismantled when their work was done. So it was with Road Camp No.2 at Rocky Hill. When the work was completed, the stone crusher was returned to Princeton and needed items were moved to Monmouth Junction for use at Road Camp No. 2A. This new camp was set up to build a new road called the Trenton/New Brunswick Turnpike, part of a much larger project known as US Route 1.

From a Lenape path to major roads supporting a much more heavily populated area, the roads that connect to Blawenburg have borne much traffic over the years. In current times, people wonder if the roadways are sufficient for the greatly increased population and commercial development. Only time will tell, but one thing is for sure. Any new road construction in Blawenburg won't widen the road thanks to the village being on the National and State Registers of Historic Places.

FACTS

1. Horses were in America for millions of years, but they became extinct about 10,000 years ago because of the loss of food during the Ice Age. They returned in the 16th century when Spanish explorers brought them to Mexico. Horses mainly lived on the plains and in the western part of America, thus it took a while before indigenous people in the northeast could use them. They often used dogs to carry their items from place to place.

2. Turnpikes are roads that charge tolls. Pikes were poles that blocked the traffic on a road. When you paid the toll, you turned the pike and continued on your way. Not all communities actually charged a toll, instead paying for the road with a special tax. It's unclear whether Blawenburg actually used pikes to block their portion of the turnpike.

3. Paving material used for roads in the early 20th century was called macadam. It was crushed stone bound with tar.

4. Route 206 was given a local name within recent years. It is also known as Van Horne Road in Montgomery Township. It is named for the land speculator who subdivided and sold the vast parcel between Rocky Hill and Province Line Road in the former village of Stoutsburg. The Van Horne property included all of Blawenburg.

5. The original Bolmer house still stands on the southwest corner of Routes 206 and 518. It now houses a bank and other offices.

SOURCES

Information

Much of the information in this blog came from previous Tales of Blawenburg blogs and local newspapers such as the Courier News and New Brunswick Daily News from the period between 1910 and 1922. Thanks to Ken Chrusz for his diligent newspaper searching.

Trap Rock Quarry - https://www.mindat.org/loc-158649.html

Pictures

Route 518 1900 – postcard image

Route 601 – D. Cochran

Bolmer's Corner construction – Road camp literature

Road camp No. 2 at Rocky Hill – postcard image

Editor—Barb Reid

Copyright © 2024 by David Cochran. All rights reserved.

Blog email: blawenburgtales@gmail.com

Blog website: http://www.blawenburgtales.com

Author website: http://www.dcochran.net

Comments